The Swedish education system aims to ensure equal access to high-quality education for all. Under the Ministry of Education and Research, five national agencies are working to achieve the goals. The National Agency for Education (Skolverket) plays a major role in monitoring school performance as well as the completion rate of schools. The Swedish Schools Inspectorate (Skolinspektionen) assesses the quality of schools and teachers on a regular basis. The National Agency for Special Needs Education and Schools (Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten) ensures opportunities for the same quality education for individuals with disabilities. The Swedish National Agency for Higher Vocational Education (Myndiheten för yrkeshögskolan) assesses labor market demands for workforce education.

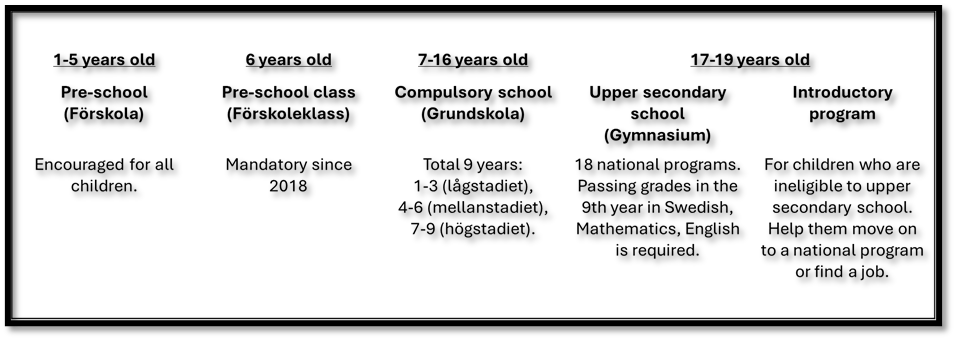

A unique feature of the Swedish education system is that it is free from preschool to university. School materials, e.g., textbooks, and meals, are covered as well. In general, children are allowed to start preschool from the age of 1 to 5, and they are required to attend a preschool class at the age of 6 which is a preparatory phase of compulsory education. Afterward, compulsory school education continues from 7 to 16 years old (9 years total). The majority of children continue to study at upper secondary schools from the age of 17 to 19 years old (3 years total). To get admitted to an upper secondary school they wish to attend, they need to attain good grades at the end of compulsory school education (in the spring of the 9th grade).

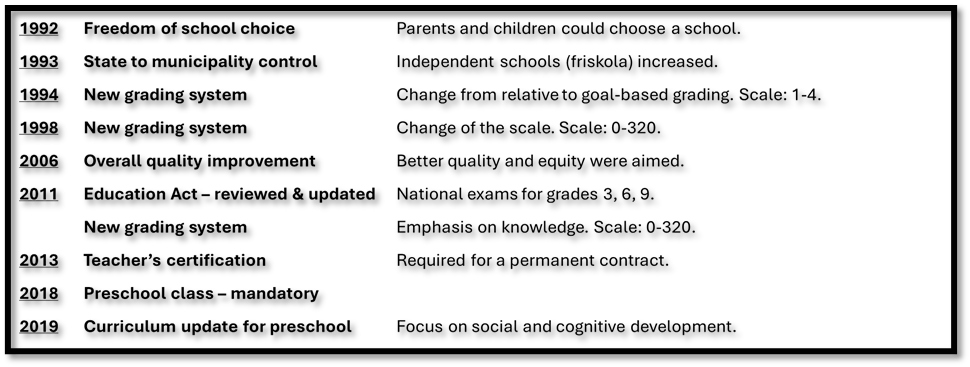

Since 1990, numerous reforms have been implemented. Now, in compulsory school education, parents and children can choose a school to attend. Around the same time, the administration of schools was shifted from the state to local municipalities. These reforms decentralized the Swedish compulsory school system and it is deemed as one of the causes of the inequalities in academic performance (1,2). The inequalities in academic performance are partially attributable to the unequal distribution of good-quality schools and teachers which were the outcomes of decentralization. Freedom of school choice enabled children of affluent parents to choose to go to better quality schools and on the other hand, children of not affluent parents go to schools close to their residence regardless of the quality. In addition to that, the number of private schools increased, and they are, although they are managed by municipal funds and obligated to align with the national curriculum, attracting more students by lowering their grading threshold which is considered as “happy grading”. The grading system has changed multiple times in the past 30 years and that might have contributed to the gap in academic performance as well. Especially since 2011, more emphasis has been placed on knowledge and that is assumed to affect negatively students with immigrant backgrounds. Besides these potentially negative reforms for the gap in academic performance, a number of reforms have been made to improve the quality of education, e.g., certificate requirement for teachers to get permanent contracts, mandatory preschool classes, and updated curriculum for preschool.

As aforementioned, gaps in academic performance between native and immigrant students, are concerning (Find more in Academic performance in Sweden). To reduce the gap Sweden has taken many measures. For example, in 1970, a salaried language training program with 240 hours started being offered to immigrants. Although the program did not persist as a salaried program, a free language program is still available to all immigrants as Swedish for Immigrants (SFI). In addition, there is a program called Mother Tongue Tuition which ensures students take courses in their native languages at schools. It is based on the evidence that children can develop skills in the second language more efficiently when they get support in their first language (9). Indeed, language is deemed as one of the most important factors for immigrant students to perform as good as other students, and invested in a great extent. However, these are seemingly not enough, and more evidence-based policies and programs are warranted (2).

References

1. Rolfe V. Exploring socioeconomic inequality in educational opportunity and outcomes in Sweden and beyond [Internet]. University of Gothenburg; 2021 [cited 2024 Jan 24]. Available from: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/68166

2. Taguma M. OECD Reviews of Migrant Education: Sweden 2010 / Miho Taguma … [et al]. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2010. (OECD Reviews of Migrant Education).

3. Skolverket. Swedish grades [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2024 Feb 8]. Available from: https://skolverket.se/download/18.47fb451e167211613ef398/1542791697007/swedishgrades_bilaga.pdf

4. Skolverket. Educational equity in the Swedish school system? A quantitative analysis of equity over time [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2024 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.6bfaca41169863e6a65b2f3/1553965825706/pdf3322.pdf

5. European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. Country information for Sweden – Legislation and policy [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 8]. Available from: https://www.european-agency.org/country-information/sweden/legislation-and-policy

6. Berglund J. Education Policy – A Swedish Success Story? Educ POLICY.

7. European Comission. Eurydice, Fundamental principles and national policies, Sweden [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 9]. Available from: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/sweden/fundamental-principles-and-national-policies

8. Skolverket. Curriculum for Compulsory School, Preschool Class and School-Age Educare – Lgr22 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.skolverket.se/publikationsserier/styrdokument/2024/curriculum-for-compulsory-school-preschool-class-and-school-age-educare—lgr22

9. Berglund J. Education Policy–A Swedish Success Story?: Integration of Newly Arrived Students Into the Swedish School System. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung; 2017.