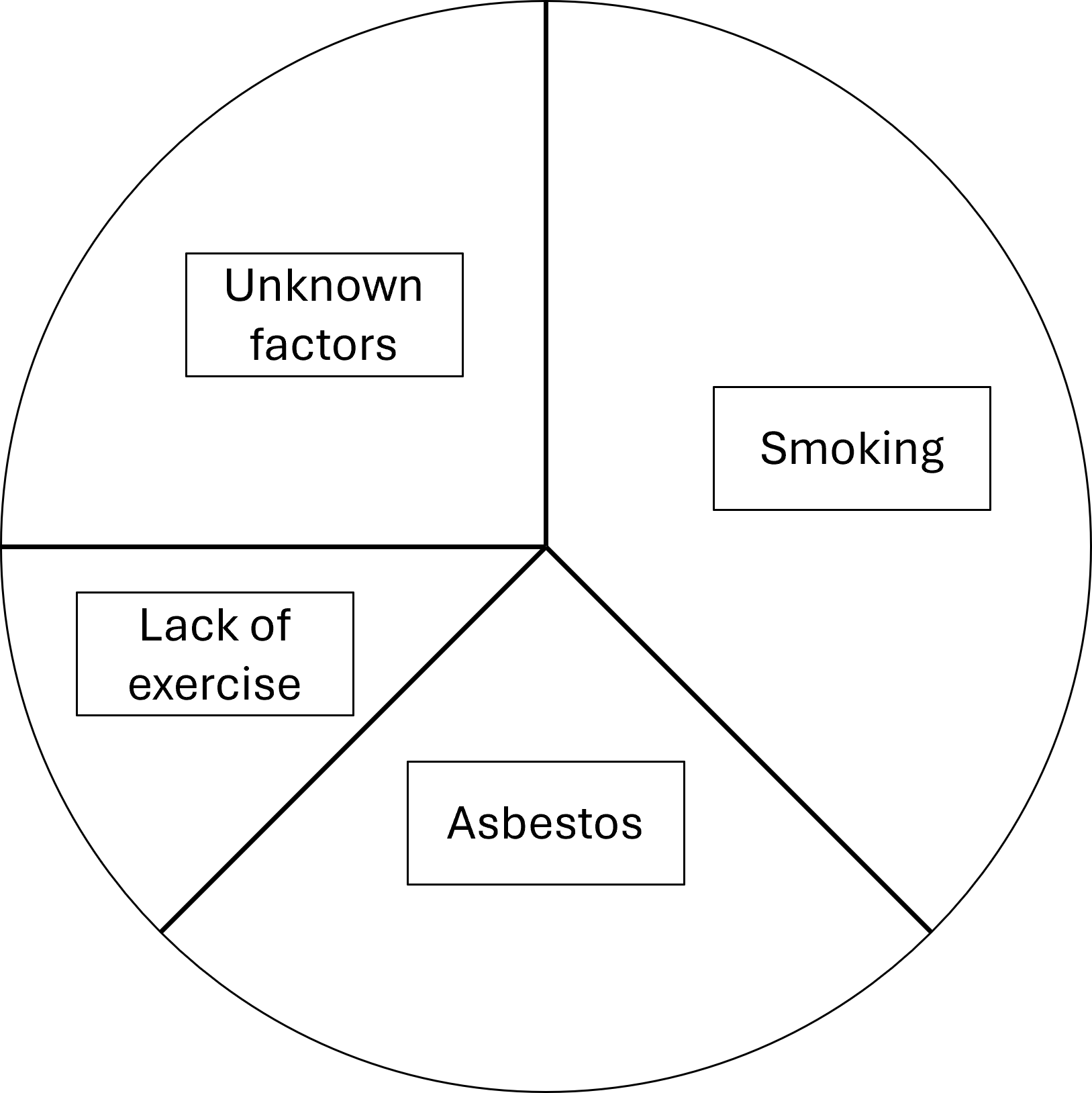

Identifying the cause of a disease is one of the central aims of epidemiology. “Smoking causes lung cancer” may be the most well-known public health statement. However, we know that not all people who smoke will develop lung cancer. Therefore, the statement can be interpreted as “Smoking is a causal component for lung cancer”. Or it can be rephrased as “Smoking increases the risk of developing lung cancer”. These statements imply that smoking is not the only cause of lung cancer. There are many other causal components. For example, exposure to asbestos, lack of exercise, and genetic propensity are known to increase the risk of lung cancer. In addition, there must be numerous unknown factors that increase the risk of lung cancer. This can be described in a causal pie chart (Figure 1). It is referred to as the “sufficient cause component model” [1], and helps us understand multifactorial causal mechanisms of diseases.

Each slice of pie represents a causal component. An important thing to be aware of is that all causal components do not have to be present. When certain causal components are sufficiently present to give rise to a disease, one develops the disease. For instance, some people who smoke but are not exposed to asbestos develop lung cancer. Other people who do not smoke, are not exposed to asbestos, but lack exercise develop lung cancer. In this sense, causal components can be categorized as necessary components and sufficient components. Necessary components are always present in all individuals who develop diseases. For example, to develop lung cancer, one obviously must have a lung. On the contrary, as abovementioned, asbestos exposure may not be present in all individuals who develop lung cancer. It would play a role as a component to suffice the conditions for one to develop lung cancer. In epidemiology, we generally investigate a group of people rather than a single individual, and therefore, we would be able to identify if a component is necessary by investigating whether it is present in all individuals with a disease of interest.

When we know certain components are present in many individuals with a disease of interest, we may want to argue the strength of their causal effects. If smoking was present in a greater proportion of individuals who developed lung cancer compared to asbestos exposure and lack of exercise, one may be inclined to state that smoking is a strong factor for lung cancer. However, the important caveat is that this does not mean that smoking is a strong factor in the biological sense. For instance, if our study population is rural residents who are rarely exposed to asbestos and other possible risk factors, as well as smoking is very common, the effect of smoking on their lung cancer would appear very strong. On the other hand, if our study population is urban residents in a specific area who are often exposed to asbestos and other possible risk factors, but smoking is relatively uncommon, the effect of smoking on lung cancer would appear weaker than that among rural residents. Therefore, depending on the population of interest and the distribution of other causal components, one component can appear as a strong or weak factor.

Reference

1. Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: An Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.