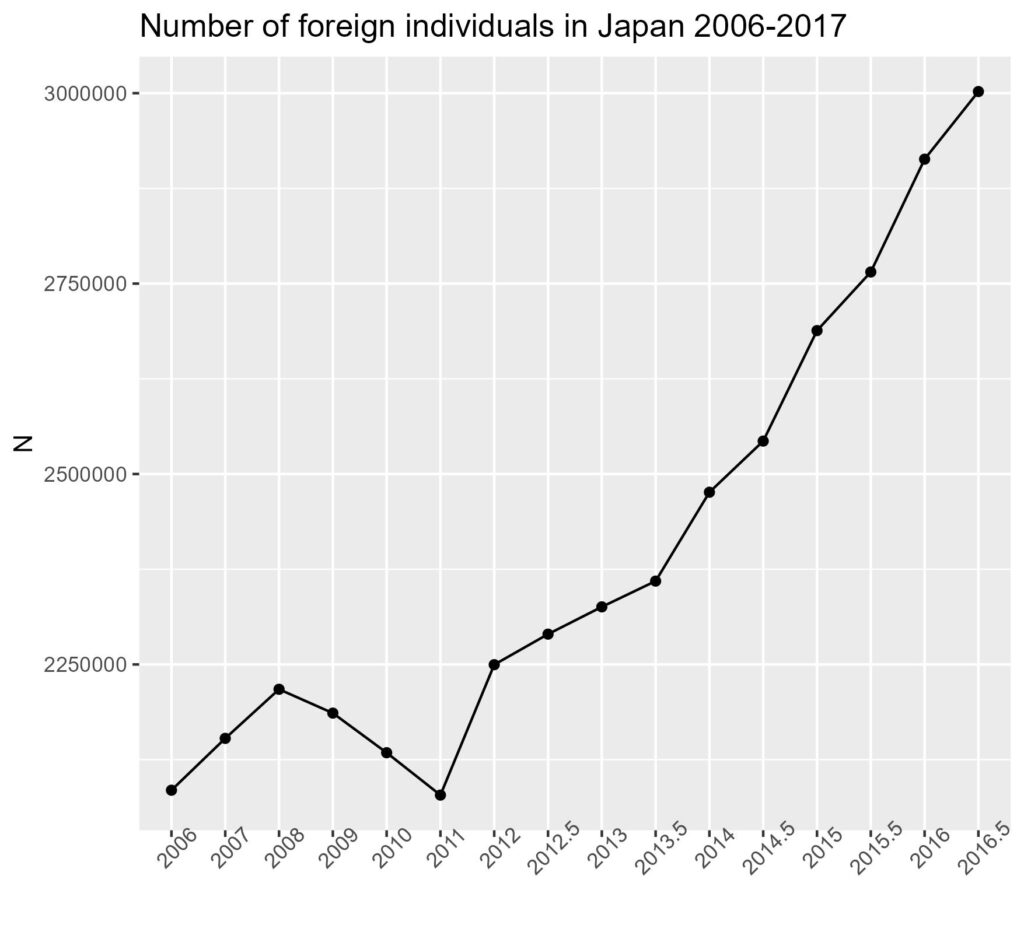

There are approximately three million foreign individuals in Japan, which is 3 % of the population [1]. In comparison to other OECD countries, the proportion of individuals with foreign backgrounds is low (OECD average: 10 %). Japan has started improving migration and integration policies only recently to attract more labor migrants to compensate for the labor force shortage. Until recently, the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) was one of the only options for migrants to come and work in Japan. However, TITP allowed migrants to stay in Japan for up to five years and expected them to go back to their home countries. TITP was highly criticized as it put many migrants in vulnerable states, family reunification was not even allowed, and as a result, exploited them for the labor force at factory, construction, and agriculture work with minimum wages.

Apart from TITP, many foreign individuals come to Japan as international students at vocational schools or universities and with special work permits called Engineers / Specialists in Humanities / International Services. However, it remains challenging for international students to gain employment in Japan due to the nature of the Japanese job recruitment system. Specifically, it is common for students to start applying for jobs one or two years prior to their completion of studies. This makes it difficult for students who are abroad to get an employment contract. Timing of job applications is critical and therefore, if students miss the timing, the chance of gaining employment can decrease considerably. The situation has been improving gradually with the help of the Japanese Student Service Organization (JASSO).

On the other hand, many migrants with permits for Engineers / Specialists in Humanities / International Services tend to stay for a long term. Approximately 40% of high-skilled migrants tend to stay in Japan.

Attaining permanent residence in Japan though, is challenging, for example, one has to stay in Japan for at least 10 years to become eligible. In 2012, the Point Based System (PBS) was introduced to help high-skilled migrants become eligible for permanent residence within less than 10 years.

In 2012, within Shinzo Abe’s government, attracting foreign skilled labor migrants was emphasized as a political agenda. While PBS was one of the measures, migration and integration policy has not been actively ensured for a while. In 2018, the integration policy was officially formulated for the first time, i.e. Comprehensive Measures for Acceptance and Coexistance of Foreign Nationals. In 2019, the Specified Skilled Worker Programme (SSWP) was introduced to attract more labor migrants in nursing care sectors.

It is expected that the number of migrants is going to increase and Japan is going to be more lenient for migrants to stay for a longer term.

At the same time, numerous challenges need to be addressed. For example, migrants are challenged to integrate into Japanese society due to language and society’s attitudes toward migrants. Japanese language education is provided by the Japanese Language Institute but the quality is not ensured, and there are limited opportunities for migrants to train Japanese language in their residential communities. In addition, Japanese society refers migrants as “foreigners” rather than individuals with foreign backgrounds, which may make migrants feel alienated. As a result, many migrants including those who came to Japan since 1990 from Brazil and Peru with Japanese ancestry backgrounds tend to segregate in certain areas, and make it difficult for them to integrate into the main stream of the society.

In 2024, a new government was formed and the conditions for immigrants to enter and stay in Japan are expected to improve. However, it is important to learn from other countries to “integrate” immigrants into society adequately so that migration can be mutually beneficial for Japanese society and migrants themselves.

References

[1] OECD. Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Japan 2024. OECD 2024. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/recruiting-immigrant-workers-japan-2024_0e5a10e3-en.html (accessed November 2, 2024).

[2] Statistics Bureau of Japan. Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan. Portal Site Off Stat Jpn 2020. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en (accessed November 22, 2024).